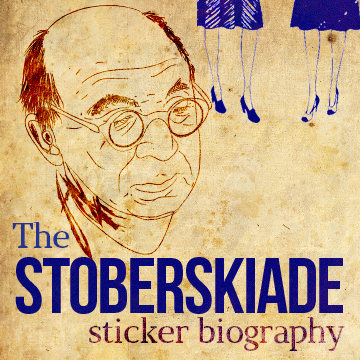

The Stoberskiade (ENG)

(…) I remembered him from before, when he was selling pretzels here on the corner, by Drobnerówka, in the beautiful, wooden pavilion that used to exist back then. That must have been in the early 1950s.

(…) I remembered him from before, when he was selling pretzels here on the corner, by Drobnerówka, in the beautiful, wooden pavilion that used to exist back then. That must have been in the early 1950s.

And I remembered him selling those pretzels because he was a real character, a short guy in glasses, with blue eyes.

He told me that he dropped out of middle school before the war because he wanted to train his body and soul — he was living in Krzemionki, in a cave of sorts, and he carried people across the Vistula River in his own flat-bottom boat. He did that until the residents of the Dębniki area came and attacked him during the night, because they thought he was a sorcerer cooking up some sort of devilry.

(…) before the war he made a trip around Poland, on foot, because he rejected both the tram and the train.

His backpack had rice and a gas cooker, but at one point the cooker broke and he had to eat the rice raw — this gave him volvulus and he lay in some bushes, somewhere up in the Pomeranian region, until it passed.

He also went on foot to see his fiancée in a village during the occupation, he even walked to Zakopane — two nights and one day, or one night and two days, sleeping where he could, by the roadside.

Once he turned up in Zakopane bathed in sweat, he had forged through an icy stream, got leg cramps, the highlanders pulled him out, laid him out in the attic, and he lay there hungry for a few days until the cramps passed.

He often told me such stories about how tough he was because he had a complex about his manhood. His masculinity had no outlet, because he was ugly, and the girls only liked him because they could take his money, but none wanted to stay with him.

He smelled bad because he was a diabetic. The stink in his apartment was awful, he tried to temper it with tree branches and juniper, but nothing worked. The dirt, the stink, the darkness.

And there he sat, covered in rugs, because he was always sick, he would doze off, write, doze, write, then go out, go on visits to his friends' apartments, mostly to beautiful married women (he was drawn to feminine beauty).

(…) great quantities of filthy sheets on the bed, where he reclined or lay and wrote, in the winter he kept his legs moving for warmth, he also warmed his legs with newspaper.

I remember a reading he gave at a dorm, I was sitting there with him and Czycz — and I noticed that some girls were staring at our legs under the table and laughing, nudging each other. Jaś was sitting between Czycz and I, wrapping his legs in newspaper.

He was walking down Krupnicza in an unbuttoned overcoat and a hat — his gaze terrifying — and in front of him was a very famous professor from a local university. The students nodded at the professor on their way into town, the professor was too haughty to nod in return, but Jaś nodded, because he wasn't certain if they were nodding at him...

He was down-at-heel. His friends once wanted to give him a shave and a haircut — hair grew from his ears and nose — but he had no desire to tidy up, he believed that it was talent, not clothing, that was important. After he dropped by we had to air out the apartment.

We always gave him tea, bread, soup, he lived off of what people gave him, because he refused to cook for himself.

He always had a bun in his pocket. He was very hard on himself — he was an infidel, but a saintly infidel.

Jaś had practically no need for money, he lived off of coffee, tea, and milk, clothing was given to him, so he gave his money to girls, who loved him for it: because he was good, and because he gave them money.

He lived among women and married couples, so rumors began spreading, not malicious ones, just the spread of human vices, and about Jaś himself. He was fond of saying he would write the whole truth about himself, the whole truth.

It was about his sex life, which was non-existent, but which he dreamed of having.

There were two owners of second-hand shops on Grodzka and Sławkowska, the richest folks in Krakow, who liked to hold little orgies. Jaś joined in once. He said that the girls undressed one of the men, in a fog of alcohol, but Jaś would not allow himself to be undressed.

He longed for contact with women, which is why he walked around kissing them, even my wife: "Just on the cheek." He longed for the feminine body. He seldom spoke, and when he did, he stuttered.

He would appear around eleven in the morning, enter, sit down, pull out some bread.

"Jaś, have some soup." "Just a touch, because I was visiting what's-her-name, her husband liked me, no jealousy; she was so pretty once they used to paint her, and now she's got a belly."

He worked out, he exercised his body, because he wanted to be forever young.

When girls were around he stripped to the waist and showed off his build — he had a strapping chest, speckled with gray hairs.

Jaś never studied, he only exercised, and before his exams he gave up and lived in a cave, where he worked out by lifting stones.

At the end of his days he was walking very badly, always stumbling; he had a limp.

(…) he described Krakow's families, so his work is a mine of information about life in Krakow in the 1950s and 60s.

He heard many hurtful things from his sister, who once told him: "I was the only one in our house who was a man"; but what saved him was that they published his work, he was a writer.

He came to have a talk and to meet a girl. "So, I'm Jaś, Adam will tell you" — he lowered his eyes...

(…) I knew what would come next, they were all somehow similar. This one was a bit too gossipy, spreading word that someone had cheated on so-and-so, or beaten someone, that she didn't like her, and this one doesn't like the other — a provincial, small-town sort of atmosphere.

He wanted to be a bit like a hermit who would come down to the people to help them.

He began his route in the morning, and it took him more or less all day. He would start conversations like: "You know, that girl..." — with whom she drank coffee, whom she met.

He often also asked his trademark question: "Well, you need a little money? I can lend you some."

Jaś sometimes spoke, sometimes he nodded off, then he'd wake up forty minutes later and say: "As long as I'm in the neighborhood, I might as well pop in on so-and-so."

He wasn't the talkative sort, something had to really intrigue him to get him going.

He was introduced to me in 1960, on Krupnicza Street, in the Writers' Home, as the oldest member of the Young Polish Writers' Circle.

He acted as though he were excusing himself for living, or at least that he was taking up anyone's time with his meager person.

He was considered a weirdo, but he was one of the nicest weirdos I ever met.

He was defenseless: he wanted to live, to write, not to bother anyone. In general he never announced his visits to friends. He came, entered, and said: "Well, here I am." And he sat down.

Most often he said nothing, and then some effort was required to get a conversation going. The best thing was to wait it out.

He spoke of the simplest everyday events, and most enjoyed gossiping, that he had been at Iksiński's house the day previous and there he heard such-and-such.

For him life, including literature, was something in between reality and gossip.

The way that he, as a timid sort of man, showed his interest in life and people brought him close to them.

He circulated among them, listened to opinions about them, had his own opinions, but it seems he thought it was indecent to devote too much attention to his loved ones, it would be a kind of incursion.

His observations on those near to him were apt, and he had a certain fondness for rumor-mongering, in the sense that he spread gossip from place to place without minding the consequences.

It was like he tried to buy his way into a new conversation with the coin of what he had just heard.

One of his traits was total indifference in terms of political and public life — he just negated it.

His was a psychological realism, he saw people through their details, through their impulses, often through the words that slipped out.

He was a very scrupulous observer, to the extent that it sometimes became a kind of vivisection.

Recognizing themselves, often correctly, as the sources of some of his tales or prose, some saw this as malicious, but this was generally a sort of kindliness. As if he didn't realize that something he had heard, something he passed on, could ever harm someone.

He thought that since he loved the world, the world should love him back, and he didn't stop and wonder if someone was pleased with his behavior or not.

(…) he felt at ease, he was grounded, comfortable, he always walked the same paths, among the same people.

He showed up a bit breathless, without notice, and said: "Well, here I am."

If he came across someone more forthright he was sometimes refused entry, but this didn't bother him.

His world was his, absolutely his own, autonomous, though his loved ones were allowed to enter.

They were a context of sorts, mainly a psychological one, for his personal feelings. I would say that he needed his loved ones as sparring partners in his everyday life.

After the war he worked in the gas works for a long time, and then, when he began writing, they published him, and he received money for his books.

When they began publishing his books he started to believe that he was a wealthy man. Sometimes he got mere pennies, but with his absolute bare necessities he was able to save those pennies so that they were enough for a time.

(…) he reminded me of a holy vagrant out of St. Francis, especially since he adored people and animals.

He expected nothing from the world apart from being published — though even in this he was none too demanding.

He was remarkably disinterested.

(…) he never attacked anyone, he wouldn't have known how to, nor could he defend himself. If someone hurt him, he didn't bear a grudge.

He could hear someone speak badly of him and then behave, upon the next encounter, as if nothing had happened between them.

He owned next to nothing: old, very simple household appliances, old chairs, an old table, a plate, a bowl.

He had his own inner life, into which he sometimes drew those he cared for.

I believe that if he had owned something that mattered to him he would have felt a loss of personality, a diminishing of his sovereignty.

I sometimes arranged him a union grant, but I really had to convince him to accept it.

He would take it saying: "Well, money sure is strange." And I: "What's so strange about it? Many literary writers take grants." And he: "Well, sure, but those are important people, and I'm not."

At times one got the feeling that he wanted to negate himself to some degree.

He made way for the world to keep from being stepped on or from getting too deeply involved. He didn't want to get in anyone's way, he wanted to maintain his freedom, his dignity, his independence. This is why he upheld the strictest privacy.

He treated his own life utterly privately, wanting to conceal it and keep it for himself.

I don't think there's any mystery here, he wanted to live as an "everyman," and so he did, not exerting himself on this count. He visited acquaintances if they were around.

He appeared unexpectedly in Astoria, the writers' house in Zakopane, for example; they gave him a place to stay and served him dinner.

I think that constant inertia would have been the death of him — he sat boarded up in his hole and suddenly felt an unconquerable urge to take a trip around Krakow, or somewhere further.

He recorded every detail of his wanderings, things that a person caught in the daily grind wouldn't notice.

There are people who can record reality in a way that is both ordinary and extraordinary.

He had no need for more complicated meals. He seldom came to the cafeteria of the Writers' Union, and apart from that he had a meager diet — for instance, he would buy himself a cabbage and boil it.

(…) his wanderings made up for all those years he spent sitting in the gas works.

His feelings were, I take it, mostly disinterested, mainly based on the fact that he heard people's confessions.

He was a man of few words, but he knew what to say to comfort others. Women married to writers were not always happy, so they were happy to confide in him, and he talked to them: "Well, don't you worry. Well, guys are just like that."

(…) he lived other people's lives, his own too, and above all, but also other people's.

He had no family, so he often lived another person's life, and in so doing he had, perhaps, moments of satisfaction of finding that those "normal" people weren't happy either, and had many problems.

A holy vagrant who eked out his existence, not in a pathetic way, but with a dignity of sorts, he wanted to get something out of it, if only the chance to touch Mrs Czycz's knee.

There was a handful of people whom he trusted, whom he was certain were tolerant toward him and wished him well, or so he assumed.

These people he hand-picked and visited their houses, taking a winding route, by no means the most direct way.

He would sit for an hour or two, saying: "All right, that did me well — off I go." And he went. If he had the urge to pay someone a call, so he did.

If he didn't show himself to people, he wasn't there at all.

He was an utterly private outsider.

(…) he was truly a therapist for hormonally disturbed housewives of all stripes, for all species and types of women, dames, broads, lasses, ladies, and other, more workaday girls.

He wandered through Krakow's apartments and artists' studios.

He dropped by the middle-class houses for supper, and the artists' studios for conversation. It isn't true that he would only sit in silence when he came, just observing.

I often met him in various places, but never in bars.

When he came to visit he always asked for something warm to cover his legs. I had a goat's skin in my studio, he often used it.

As he once told me, he walked far as a young man. To Szczawnica, Nowy Targ, Biały Dunajec.

My late mother-in-law told me he was a weirdo; she would laugh at the fact that Jaś once visited them wearing two different shoes.

It's true that he attached no importance to money, because when he had it he would lend it to someone else, most often Piotr Skrzynecki, who never paid him back.

My father-in-law told me that Jaś was taking care of his sick brother, that he was visited by women who brought him things to eat (most often pierogi).

When he was sick and didn't leave the house, my father-in-law went shopping for him (only the basics).

He was witty to the highest degree, he was an educated man, very well-read.

(…) he was a sensitive man, so he was weak, very good, distinguished, from another epoch. He had many hardships, many adversities in his life, he lived through two wars.

(…) he had a balance disorder. When he walked down the street he swung his arms to keep it under control. He was muscular, at any rate, quite strong. He needed solid shoes to keep him to the ground. He didn't like carrying things, because they set him off balance.

Everyone once in a while he had a shoemaker make him heavy ankle-boots — they helped him walk.

He always walked in the same pair, summer or winter, and finally it got so that his toenails grew out and hooked like the talons of an eagle, they became ingrown and caused all sorts of unpleasant ailments.

He was always cold. All his acquaintances — and there were many of them — had a leg rug prepared for him, even during the summer. The normal body temperature is 36 degrees, while his was 35 and a bit, which was a kind of medical anomaly, causing him to constantly feel cold.

I visited him once on Paulińska Street, he was sprawled out in his old wooden bed, saying that his liver hurt. I asked him a few questions and it turned out that he was plagued by the aftertaste of garlic. I discovered that for the past ten years he had eaten a whole head of garlic every day...

He didn't eat much when he visited — if I made him a plate of sandwiches, he would say no, no, two were enough. He ate only small portions of meat. He would not tolerate alcohol or tobacco smoke.

(…) one eye was far-sighted, the other near-sighted. His low temperature astonished doctors.

His room was in a horrible disarray, the window was always closed and dirty, with rags stuck between the panes to keep the wind from blowing in. In the corner he had a bed strewn with sheets.

His funeral was incredible — I was very moved. People came in great numbers, I kept to one side. There were family, friends, acquaintances from all kinds of communities: actors, artists, engineers, doctors, and many others. The only thing I didn't see was a priest — the drunks more stood out.

The only thing I didn't see was a priest — the drunks more stood out. It was a very serious funeral, people were focused and emotional. When I was already going to leave, alongside me appeared Professor Adam Hoffman, a famous painter, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, and he said only three words, very apt ones: "He slipped away."

The adoration was a bit comical — it didn't fit his appearance, his old-man's posture. Sometimes I thought that he must have looked that way when he was born.

It's a fact that he didn't change over the years. He went around in the same clothes. He was a minimalist who required very little to live.

He had a set program, where he dropped by, where he ate dinner, where he ate cheese, and where again he would get something to drink.

When he dropped by he told us not to give him anything, because he would be eating elsewhere, and he mentioned a name. He always made certain not to put anyone out. He didn't eat with poor people like us, because he didn't want to take advantage of a friend's good nature.

His life was more or less settled, so he just wrote. After breakfast he sat down and sat throughout the late morning in front of the typewriter — he had to write at least a page or two a day.

It was a hole, and a dark one. I was there once to borrow a book, and he invited me to come see his apartment. I didn't really want to go, because I was afraid he would try to put the moves on me, but Staszek chased me out.

It was utterly harmless, the way I see it now — it was even funny. I got upset, and Staszek just laughed. At the time I didn't find it so humorous, I don't suppose anyone cares for such one-way affections. I liked him a great deal, but there was nothing erotic in it.

It's true they blabbed everything to him, most often about quarrels with their partners. And he tried to comfort them, so he fondled and embraced them — this was a real boon for him, because they wouldn't have let him do it for no good reason.

He was simply a good man. He loaned money, he brought books. Maybe his listening was a way of getting information from women that he needed for his writing.

In those days I didn't think that way, because sometimes he really drove me mad. And Staszek kept prodding me on, which made me furious with him. Staszek said: "But he's so nice. Smile a bit at him." And I flew into a rage: "I can smile, just don't let him touch me."

I think so, because he was totally non-threatening. If he had behaved like a seducer, if he had been handsome and eloquent, that would have been another thing altogether.

He definitely did some kind of business. He knew about business, even wrote something on the subject.

I don't know. I only heard about his trips to Zakopane on foot. He walked a lot, which is maybe why he always was in shape — never becoming skinny or gaining weight.

And he didn't eat much: a hunk of bread and some cottage cheese were enough. He was a very modest sort of fellow.

People seemed to meet him by accident, as it were. Someone would meet him somewhere, then return, and meet him again.

(…) he never sat by the table. As a rule he sat off in the corner and seldom spoke. He generally responded to questions, but would not start a conversation on his own.

(…) he generally left early. Sometimes he said: "I've got somewhere else to drop by," and this was true. We knew that his habit was to sit here and there.

(…) after the first visit, he would drop by from time to time.

He never said he was coming, I don't suppose he owned a telephone. If he did have one, he didn't use it. At any rate, he would just descend on you, from out of nowhere.

(…) nor was he a stranger to mental deviations. He was a remarkably secretive fellow, yet very honorable and ambitious.

Janek was a very delicate, sensitive, and humble man; he lived as though apologizing for living.

(…) what can you really say about a person who is entirely locked up in his own world.

He never went out begging, and didn't like to accept money, he could even get offended if someone offered it to him.

It was his humility that stood out – he would have been happiest in a magic cap: "I'm not here, you can't see me."

He would drop by, spread a little gossip, then doze off, have a bite to eat, and walk on. He liked to sit there in silence with Father.

(…) he became an everyday part of our home landscape (…)

He was a man who existed in a beautiful way. He was a literary figure, which is how he was perceived by people who didn't know much about him.

(…) you couldn't even impersonate his accent, which came from the Zwierzyniec lumpen proletariat.

He asked me for my address, and then he dropped by one day unannounced and found me at home.

After that he came regularly, at least once a week, he ate lunch or supper. What he didn't eat he stuffed in his pockets, because he felt the constant threat of hunger.

Maybe he chose those whose houses he could eat at, and others where, for some reason, he wouldn't eat. He always ate at my house, and left with pockets full of leftovers, because he stuffed whatever didn't get eaten into his pockets.

He said he didn't eat meat when he was a child. He threw it defiantly out the window, screaming at his parents: "I will not eat a pig!" At my house he wasn't a vegetarian. He ate normally.

We met long before the Martial Law period. He was already old when I met him, and young at the same time. He stayed young and old till the very end. He had the smile of a child and was a child inside. He even laughed like a child.

Sometimes we went to the movies. He generally chose comedies, and began laughing even while the ads were still playing. He thought that, since he paid for a ticket, he should laugh from the very start. And that's what he did, to the astonishment, and sometimes the irritation, of those sitting near us.

He was never famous, the word doesn't suit him at all.

Even Błoński borrowed money from him... Everyone relied on his money. It wasn't much, but it meant you had to pay him back, and he knew how to blackmail. He did it in a charming way, but he knew all too well what he was doing. Everyone owed him money.

He never demanded to be paid back, never mentioned it, but it was hanging there in the air.

It wasn't misery, it was a plot taken from Bruno Schulz. You entered a dark hole, and his brother — his alter ego — was living behind a screen. Eternally filthy, he lay there in an undershirt, which was sticky from the dirt.

That room really made an impression. A sack, a typewriter. Jaś didn't use sheets. There were some military coats, blankets, cloaks. A gray wardrobe, a scrap of a curtain from between the world wars, it seemed. The cobwebs were so thick you could cut them with a knife.

It wasn't misery, he was just scruffy, but he lived as he pleased. He walked around in the same clothes ever since I knew him: in a hat or a brown duffle coat and high boots, generally without laces.

He had a balance problem, he had a very unusual gait. One leg was said to be shorter than the other. I knew it was him from two hundred meters away. It was like he was "carved out of the air."

(…) he cut off one of his fingers? It was when he was working in Germany.

He was mercilessly dirty. A doctor said that if he didn't wash his hair he would have to stop seeing him, because he found it disgusting. I rubbed his head in oil, there was a layer of dirt on his bald patch, on his chest. I smeared him in the oil and then I tore it off.

He told me, for example, about his travels through the mountains. He kept away from hostels and shelters. He preferred to sleep in piles of hay. He went around to homes and asked for water or milk. He visited all of Podhale this way. His accent was inimitable.

(…) he seemed to have read everything. We even read the Koran and the Torah together, though we were irreligious.

Once, when he was in bad shape, I suggested he see a priest, but he thundered at me: "One of those guys in black? Not on your life!"

He never said a bad word about them. He never said anything bad about people in general. He only listened and debated.

(…) he sexually molested her, she told me about it herself. He caught her somewhere, kissed her hair... She said he was disgusting.

His romances were an interesting chapter. Almost every one of those women was named Krysia.

He also had a great complex about his ugliness. You can see it in his writing.

There was a portrait hanging over the bed, a photograph basically, which he had bought somewhere, and he evidently liked it: it showed a kind of fop with his hair parted in the middle, a prewar dandy. Whenever he looked at it, he laughed. He had competitions with me to see who could laugh longer. We giggled liked we were possessed, and he generally beat me.

Our middle-school class once took a field trip to Skała — he went there on foot, went back to Krakow for lunch, and in the evening he returned, by himself, to have a good look around.

As a sixteen-year-old he ran away from home for two weeks and lived in a cave in Krzemionki somewhere. He took books with him, a loaf of bread, and a few candles, but when they ran out he had to earn a bit of money and found a job digging the Vistula, carrying rocks or something.

(…) he loved wild flowers, particularly forget-me-nots, and when my mother wanted to plant some on my grandma's brother's grave, Janek wouldn't stand for it: "No, I won't let you rule my parents' grave, there have to be forget-me-nots and ferns." And so it was.

In the evenings he took a walk to see some friends, day in, day out. Every day was the same, whether it was Saturday, or Sunday, or any day of the week.

(…) he loved walking, he loved wandering on foot, twenty or thirty kilometers was no distance for him at all. He could do the same route many times over. He enjoyed the sight of nature, a dashing hare, a meadow, a forest. He said it was good for his eyes. The greenery.

They took him off to Germany to work. Snagged him in a roundup. When he was over there a machine sliced off one of his fingers, but I remember how Grandma said: "Why did you stick your finger into that machine?" "And what would you have me do for the Germans..."

He adored women, I don't know where he got it, but it was a disinterested kind of adoration, there were no great loves, just crushes. It seems there never were more powerful feelinsg in his life — if there had been, Grandma would certainly have known about it.

Janek was odd, he was lucky he lived in those days, because today they would call him a terrible freak. No car, no cell phone, no television, how does he get by? But he lived in peace, just as he pleased.

He didn't have much, because there wasn't much he needed. He would say: "What do I need that for?" He needed a kettle for boiling water and a pot to cook beans.

When the mailman came to bring his retirement benefits, his friends were sure to appear soon after, we never asked about it, at any rate, that was his business.

He didn't buy clothing, it was more like he got it from other people, he also said it pleased him that someone would come to his apartment and think: "How good it is that I don't live this way."

To assimilate with these simple folk he tried to speak their language, and he was heard saying "potaters" or "waddah."

He didn't write a last will and testament.

(…) he was an example of a professional Sunday writer on every day of the week. He was always being hosted in various houses – visiting days were not only on the weekend. Stoberski's writing is that of a guest, a friend of many homes, a companion to men and ladies.

It was thought to be a waste of ink to describe the community of artists, but he was undoubtedly a writer from such an environment.

He only really wrote of his relationships with various people, he discovered a world right under his nose that was peopled with protagonists everyone knew, and who spoke of what everyone else did.

• • •